You’ve Got Mail: Poring Over the Love Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Laura McNeal on an Archive of Romance

If you go to the Margaret Clapp Library at Wellesley College, you may encounter the exhibit of a door. You can face its immaculate varnished exterior and brass fittings.

You can go around (but not through) to see its white-painted inner side and pretend you are in the hall of a house leased to a man named Edward Barrett who had 12 children, the eldest of whom was a poet.

The door became famous in the 1930s because of a play and two movies called The Barretts of Wimpole Street, which dramatized a romance conducted largely through letters, 573 of which still exist.

Here’s part of one:

Elizabeth Barrett to Robert Browning

50 Wimpole Street: March 20, 1845.

Like to write? Of course, of course I do. I seem to live while I write—it is life, for me. Why, what is to live? Not to eat and drink and breathe,—but to feel the life in you down all the fibres of being, passionately and joyfully. And thus, one lives in composition surely—not always—but when the wheel goes round and the procession is uninterrupted. Is it not so with you? oh—it must be so.

When the whole row of houses on Wimpole Street was scheduled for demolition in the 1930s, an American woman heard about it. She bought the door. She paid to have it saved and loaded onto a ship. She donated it to Wellesley because they already owned the 573 letters.

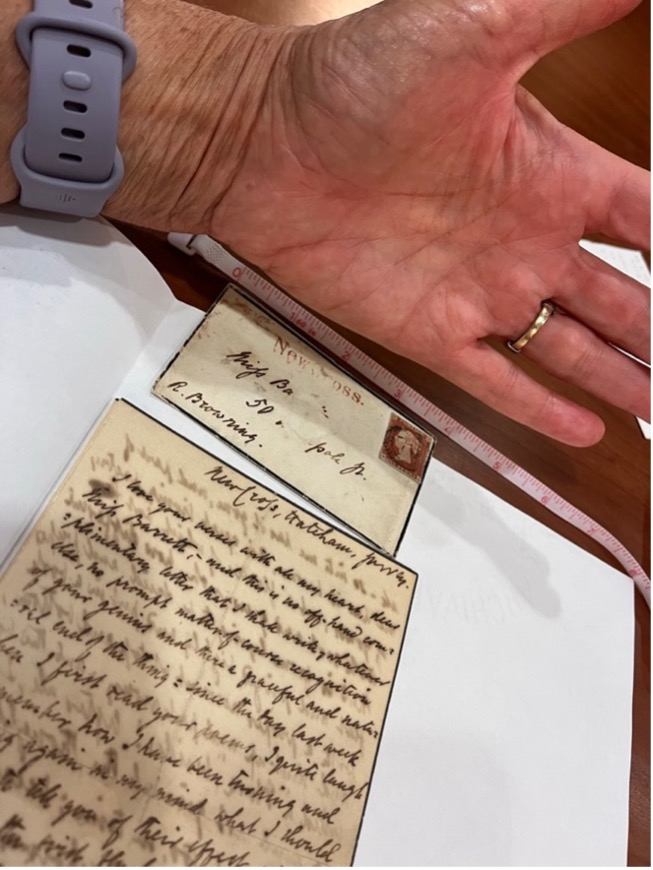

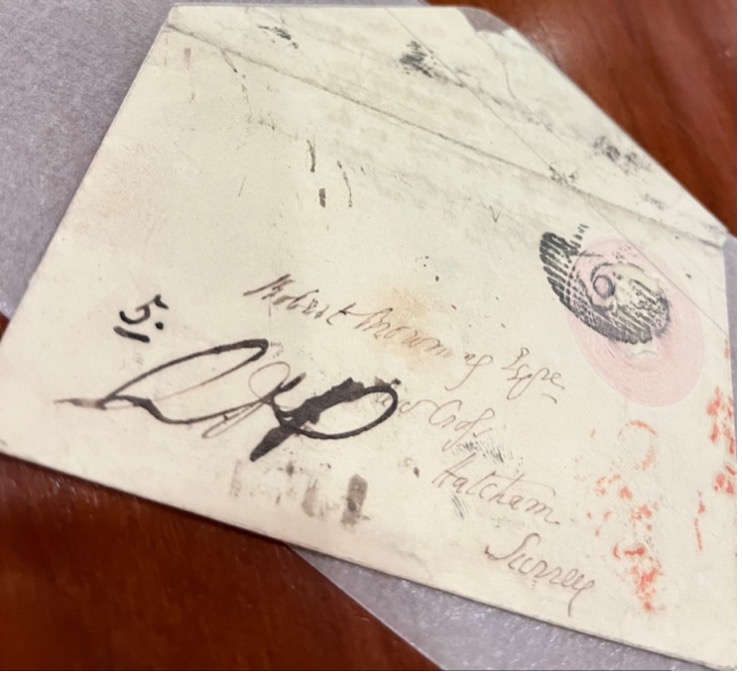

I read these letters over and over when trying to write a novel about how two people who had never seen each other could fall in love, move to a foreign country, go on writing poems through parenthood and various wars, and stay in love for the rest of their lives. I studied the way the letters looked in photographs. I zoomed in on the stamps: Penny Reds and Penny Blacks.

I learned how many times a day letters were delivered in central London in 1845 and 1846—seven, and how many times a day letters were delivered in Hatcham, where Robert Browning lived with his parents and sister—four. I read that before the invention of the Penny Red, the recipient of a letter had to pay postage. This led to people standing on their doorsteps and asking to know who wrote the letter, sort of like deciding whether to accept a collect call, another thing we don’t have to do any more.

I remember when it first became possible, in the 1990s, to buy machine-stitched quilts, how I thought it would destroy the art of making them by hand. A handmade quilt has a quality that is often called imperfection but it’s not just that: it’s the awareness of time. Time is a quality beyond and yet inclusive of material elements. The materials contain what is left of a person’s deliberate attention and persistence in the face of interruption, indifference, and self-doubt. Letters, too, are made of time, and they transcend time:

Robert to Elizabeth

Monday.

[Post-mark, May 12, 1845.]

…one day, oh the day, I shall see you with my own, own eyes … for, how little you understand me; or rather, yourself,—if you think I would dare see you, without your leave, that way! Do you suppose that your power of giving and refusing ends when you have shut your room-door? Did I not tell you I turned down another street, even, the other day, and why not down yours? And often as I see Mr. Kenyon, have I ever dreamed of asking any but the merest conventional questions about you; your health, and no more?

I will answer your letter, the last one, to-morrow—I have said nothing of what I want to say.

Ever yours

R.B.

When Robert wrote the above letter, he and Elizabeth had been corresponding for five months, and he still had no idea what she looked like. She was a shut-in, a shut-out, a go-nowhere. In 1845, London was polluted with fog and coal smoke. There were no inhalers, no antibiotics, no nebulizers, no air filters. She was 39 and felt her best years were over.

E.B.B. to R.B.

Thursday.

[Post-mark, May 16, 1845.]

…There is nothing to see in me; nor to hear in me—I never learnt to talk as you do in London; although I can admire that brightness of carved speech in Mr. Kenyon and others. If my poetry is worth anything to any eye, it is the flower of me. I have lived most and been most happy in it, and so it has all my colours; the rest of me is nothing but a root, fit for the ground and the dark. And if I write all this egotism, … it is for shame; and because I feel ashamed of having made a fuss about what is not worth it… Come then. There will be truth and simplicity for you in any case; and a friend. And do not answer this—I do not write it as a fly trap for compliments.

On May 16, 1845, Robert Browning was admitted to Elizabeth’s room by one of her sisters. He saw her for the first time, and she saw him for the first time. They heard each other’s voices. She expected him to be jolted into a perception of her as she really was–for him to see how foolish it was to think and say he loved her. Instead, he wrote:

[Post-mark, May 21, 1845.]

I trust to you for a true account of how you are—if tired, if not tired, if I did wrong in any thing,—or, if you please, right in any thing . . .they all say here I speak very loud—(a trick caught from having often to talk with a deaf relative of mine). And did I stay too long?

She replied the next morning:

Indeed there was nothing wrong—how could there be? And there was everything right—as how should there not be?

In what must have been a kind of rapture, Robert received this encouragement and went to the place we all go at least once, where we blurt out what we want from someone, which is everything, and Elizabeth, instead of being happy (he didn’t think her old and ugly!), was terrified.

She wrote:

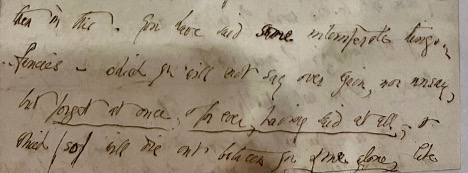

You have said some intemperate things … fancies,—which you will not say over again, nor unsay, but forget at once, and for ever, having said at all; and which (so) will die out between you and me alone, like a misprint between you and the printer…

… You remember—surely you do—that I am in the most exceptional of positions; and that, just because of it, I am able to receive you as I did on Tuesday; and that, for me to listen to ‘unconscious exaggerations,’ is as unbecoming to the humilities of my position, as unpropitious (which is of more consequence) to the prosperities of yours. Now, if there should be one word of answer attempted to this; or of reference; I must not … I will not see you again—and you will justify me later in your heart.

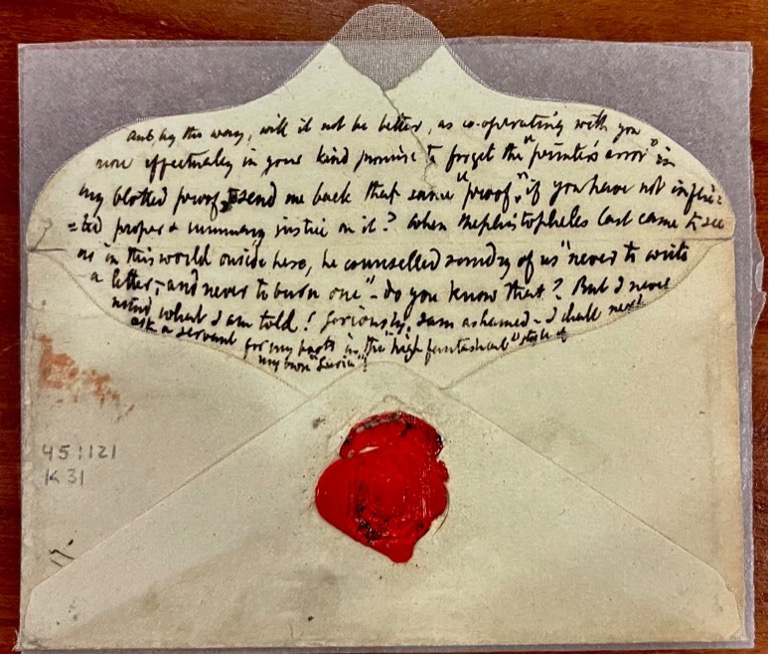

Robert burned the letter full of intemperate fancies. It is the only one they exchanged which is not saved in a box at the Clapp Library at Wellesley.

I thought I had experienced the letters fully when I read them at my desk. I thought I had absorbed their essence. And then I flew to Boston, rented a car, drove to Wellesley, parked the car, and stood in front of the transported door of 50 Wimpole Street, which was presented to the library on the 94th anniversary of May 16, the day Robert stood before the door and waited for it to open so that he could see and be seen by a mind he loved.

I sat at a table and a librarian began to bring me one letter at a time. I had to choose a small percentage of my favorites; we had only eight hours before the library would close and I would go away again. I sat holding a stamped envelope which had long ago—177 years ago–been unopened, which had been collected and crushed in a letter carrier’s bag and pushed through a door like all the other doors on Wimpole Street, the rest of which have been destroyed.

One thing you cannot understand when you see a thing on a screen is its size. Our letters are big, like us. Their letters are small, like them. They seem too small to have accomplished so much, to have survived so long.

Robert’s first letter to Elizabeth, parts of which I had already memorized, was written on paper folded in eighths, not halves. The pages had broken at the folds. The writing is very straight and legible but the ink has bled through the paper over time. It’s possible to imagine a time when you will not be allowed to touch these letters at all. They will be too fragile.

I notice different passages when I’m holding the thing itself—the real letter, which was held by a person who didn’t know what would happen in the future.

Real warm spring, dear Miss Barrett, and the birds know it, and in Spring I shall see you, really see you . . for when did I once fail to get whatever I had set my heart upon? as I ask myself sometimes, with a strange fear.

I notice that on the tiny envelope that Elizabeth uses to reply to him, someone has written the number 5 and underlined it.

Robert is already counting the letters he receives from a woman he has never seen. By the time she received her 47th letter from him, she, too, was counting. In the 47th letter, Robert wrote

…that I loved

You from my soul, and gave you my life, as much of it

As you would take,–and all that is done, not to be

Altered now.

And she, in mid-November, wrote:

The first moment in which I

seemed to admit to myself in a flash of lightning the possibility of

your affection for me being more than dreamwork…the first moment

was that when you intimated …that you

cared for me not for a cause, but because you cared for me—

And yet it was another eleven months before she dared to ask her maid to go with her on a Saturday morning to the church and be a witness as she took his name without her father’s permission. They moved to Italy, where she hoped to be cured of the lung disease that kept her perpetually indoors. She gave birth to a healthy child at the age of 43.

If I turn off my computer, the images of the letters, made of things I don’t understand, vanish. In the Clapp Library, in a paper box, the letters themselves sit in tight rows.

On thin paper, in November of 1845, Robert wrote to Elizabeth about time and human handiwork:

The sensation is like standing in the tomb at Pisa, or more like the sinopia, the drawings made before the frescos were done, the first sketch of the grand design, and the wonder of it existing beyond the death of the person who made it, seeming to place one time period inside the other, to elide the time between . . .

The door has that power, as the paper letters do, with their stamps and blotches—the first sketch of the grand design, and the wonder of it existing beyond the death of the person who made it. For nearly a century, students have been bringing love letters to the Clapp Library, slipping valentines through the slot, hoping the effort will make their words ring true, and that librarians won’t mind assisting.

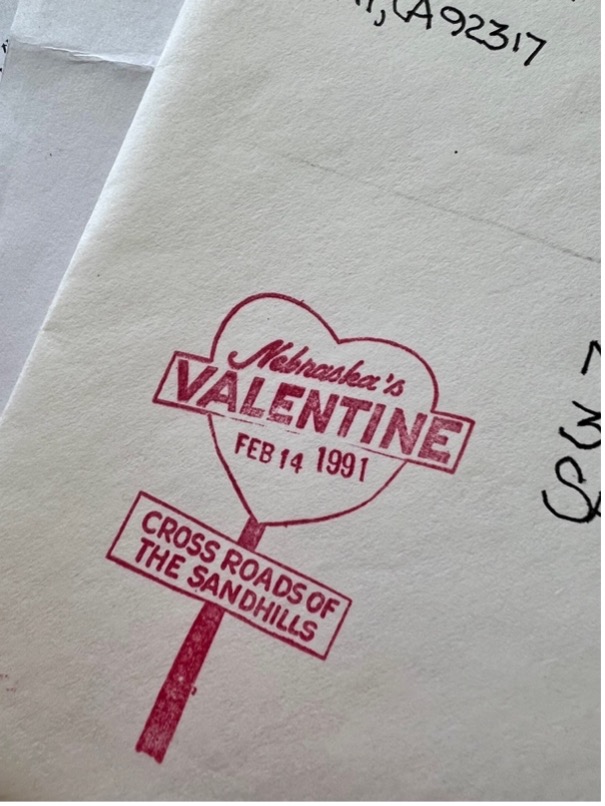

The library is closed for renovations, but you could still do what my husband did when he was not yet my husband, when he lived in one state, and I another. If you send your stamped and addressed letter in a larger envelope to Cupid’s Mail Box, P.O. Box 201, Valentine, NE 69201, they will make it look like this and send it on:

May the words within inspire a stranger to pull your mailbox from the rubble and make it a monument to love, or take you to Italy to be cured, or even just write you back.

________________________________________

The Swan’s Nest by Laura McNeal is available now via Algonquin.

Laura McNeal

Laura McNeal is the author of Dark Water, a finalist for the National Book Award in Young People’s Literature in 2010, the historical novel, The Practice House, The Incident on the Bridge, and four critically-acclaimed novels co-written with her husband Tom, all of them published by Knopf Books for Young Readers. She holds an MA in fiction writing from Syracuse University and was awarded a 2022 research residency at Baylor University.